Beyond Mapping

|

Map

Analysis book with companion CD-ROM for hands-on exercises and further reading |

What Is Object-Oriented Technology

Anyway? — establishes

the basic concepts in object-oriented technology

Spatial

Objects—the Parse and Parcel of GIS?

— discusses

database objects and their map expressions

Does Anyone Object?

— discusses

some concerns of object-oriented GIS

Observe the

Evolving GIS Mind Set — illustrates

the "map-ematical" approach to

analyzing mapped data

Note: The processing and figures discussed in this topic were derived using MapCalcTM

software. See www.innovativegis.com to download a

free MapCalc Learner version with tutorial materials for classroom and

self-learning map analysis concepts and procedures.

<Click here> right-click to download a

printer-friendly version of this topic (.pdf).

(Back to the Table of

Contents)

______________________________

What Is

Object-Oriented Technology Anyway?

(GeoWorld, September 1996, pg. 26)

Object-oriented technology is

revolutionizing

With the advent of Windows ’95,

however, OOUI’s have moved from “state-of-the-art” to commonplace. Its objects include all those things on the

screen you that drag, drop, slide, toggle, push and click. On the “desktop” you have cute little

sketches including file folders, program shortcuts, a recycle bin and task

bar. In a “dialog box” the basic objects

include the check box, command button, radio (or option) button, slider bar and

spinner button, in addition to the drop-down, edit and list boxes. When activated, these objects allow you to

communicate with computers by point ‘n

click, instead of type ‘n retype. Keep in mind that OOUI defines “a friendly

user interface (FUI) as a graphical user interface (GUI)”… yep you got it

again, a phooey-gooey.

Just about every

Whereas an OOUI dialog box is independent, an OOPS dialog box is one in

a linked set of commands depicted in the flowchart. Most modern

The OOPS flowchart captures a succinct diagram of an application’s logic, as

well as actual code. As

This topic was discussed in detail several issues ago (see Author’s

Note) within the contexts of a “humane

The full incorporation of a robust OOPS makes the transition of

__________________________________

Author’s Note: GeoWorld

November and December, 1993).

Spatial

Objects—the Parse and Parcel of

(GeoWorld, October 1996, pg. 28)

Last section suggested that there are three basic types of

“object-oriented-ness.” The distinctions between an OOUI (object-oriented user interface) and an

OOPS (object-oriented programming system)

were tackled. That leaves the third type

of “OO-ness,” object-oriented database management (OODBM, pronounced ooD’BUM)

for scrutiny this time. The OODBM

concept provides database procedures for establishing and relating spatial

objects, more generally referred to as “data objects.” Early DBM systems used “flat files,” which

were nothing more than long lists of data.

The records, or data items, were fairly independent (usually just

alpha-numerically sorted) and items in separate files were totally

independent.

With the advent of “relational databases,” procedures were developed

for robust internal referencing of data items, and more importantly, indexing

among separate data sets. OODBM, the

next evolutionary (or quite possibly, revolutionary) step, extends direct data

indexing by establishing procedural rules that relate data. The rules are used to develop a new database

structure that interconnects data entries and greatly facilitates data

queries. They are a natural extension of

our current concerns for data standards and contemporary concepts of data

dictionaries and metadata (their discussion reserved for another article).

The OODBM rules fall into four, somewhat semantically-challenging categories: encapsulation, polymorphism, structure, and inheritance. Before we tackle the details, keep in mind

that “object-oriented” is actually a set of ideas about data organization, not

software. It involves coupling of data

and the processing procedures that act on it into a single package, or data object. In an OODBM system, this data/procedure bundle is handled as a single unit; whereas the

data/procedure link in a traditional database system is handled by separate

programs.

It can be argued (easily) that traditional external programs are

cumbersome, static and difficult to maintain— they incrementally satisfy the

current needs of an organization in a patchwork fashion. We can all relate to horror stories about

corporate databases that have as many versions as the organization has

departments (with 10 programmers struggling to keep each version afloat). The very real needs to minimize data

redundancy and establish data consistency are the driving forces behind

OODBM. Its application to

Encapsulation is OODBM’s cornerstone concept. It refers to the bundling of the data

elements and their processing for specific functions. For example, a map feature has a set of data

elements (coordinates, unique identifier, thematic

attributes). Also it can have a set of

basic procedures (formally termed “methods”) it recognizes and responds to,

such as “calculate your dimensions.”

Whenever the data/procedure bundle is accessed, “its method is executed on its data elements.” When the “calculate your dimensions” method

is coupled with a polygonal feature, perimeter and area are returned; with a

linear feature, length is returned; and, with a point feature, nothing is

returned.

If the database were extended to include 3-dimensional features, the

same data/procedure bundle would work, and surface area and volume would be

returned… an overhaul of the entire application code isn’t needed, just an

update to the data object procedure. If

the data object is used a hundred times in various database applications, one

OODBM fix fixes them all.

The related concept of polymorphism

refers to the fact that the same data/procedure bundle can have different

results depending on the methods that are executed. In the “calculate your dimensions” example,

different lines of code are activated depending on the type of map feature. The “hidden code” in the data/procedure

bundle first checks the type of feature, then automatically calls the

appropriate routine to calculate the results… the user simply applies the

object to any feature and it sorts out the details.

The third category involves class

structure as a means of organizing data objects. A “class” refers to a set of objects that are

identical in form, but have different specific expressions, formally termed

“instances.” For example, a linear feature

class might include such diverse instances as roads, streams, and powerlines. Each instance in a class can occur several

times in the database (viz. a set of roads) and a single database can contain

several different instances of the same class.

All of the instances, however, must share the common characteristics of

the class and all must execute the set of procedures associated with the class.

Subclasses include all of the data characteristics and procedural methods of

the parent class, augmented by some specifications of their own. For example, the linear feature class might

include the subclass “vehicle transportation lines” with the extended data

characteristic of “number of potholes.”

Whereas the general class procedure “calculate your dimensions” is valid

for all linear feature instances, the subclass procedure of “calculate your

potholes per mile” is invalid for streams and powerlines.

The hierarchical ordering embedded in class structure leads to the

fourth rule of OODBM— subclass

inheritance. It describes the

condition that each subclass adheres to all the characteristics and procedures

of the classes above them. Inheritance

from parent classes can occur along a single path, resulting in an inheritance

pattern similar to a tree branch. Or, it

can occur along multiple paths involving any number of parent classes,

resulting in complex pattern similar to a neural network.

In general, complex structure/inheritance patterns embed more

information and commonality in data objects which translates into tremendous

gains in database performance (happy computer).

However, designing and implementing complex OODBM systems are extremely

difficult and technical tasks (unhappy user).

Next month we’ll checkout the reality, potential and pitfalls of

object-oriented databases as specifically applied to

Does Anyone Object?

(GeoWorld, November 1996, pg. 26)

The last couple of sections dealt with concepts and procedures

surrounding the three forms of object-oriented (OO) technology—OUI, OOPS

and OODBM. An object-oriented user interface (OOUI) uses

point-and-click icons in place of

command lines or menu selections to launch repetitive procedures. It is the basis of the modern graphical user

interface. An object-oriented

programming system (OOPS) uses flowcharting widgets

to graphically portray programming steps which, in turn, generate structured

computer code. It is revolutionizing

computer programming—if you can flowchart, you can program. Both OOUI and OOPS are natural extensions to

Object-oriented database management (OODBM), on the other hand,

represents a radical change in traditional

The OOBDM concept provides database procedures for establishing and relating

data objects. Last issue discussed the four important

elements of this new approach (encapsulation,

polymorphism, class structure, and inheritance). As a quick overview, consider the classical

OODBM example. When one thinks of a

house, a discrete entity comes to mind.

It’s an object placed in space, whose color, design and materials might

differ, but it’s there and you can touch it (spatial object). It has some walls and a roof that separates

it from the air and dirt surrounding it. Also, it shares some characteristics

with all other houses—rooms with common purposes. It likely has a kitchen, which in turn has a

sink, which in turn has a facet.

Each of these items are discrete objects which

share both spatial and functional relationships. For example, if you encounter a facet in

space you are likely going to find it connected to a sink. These relational objects can be found not

only in a kitchen, but a bathroom as well.

In an OODBM, the data (e.g., facet) and relationships (e.g., rooms with

sinks therefore facets) are handled as a single unit, or data/procedure bundle.

Within a

Such a system (if and when it is implemented) is well suited for organizing the

spatial objects comprising a

For years

The main problem of both OOBDM and its “vector composite” cousin comes from

their static and discrete nature. With

OODBM, the specification of “all encompassing rules” is monumental. If only a few data items are used, this task

is doable. However, within the sphere of

a “corporate”

However, each time a layer changes, a new composite must be

generated. This can be a real hassle if

you have a lot of layers and they change a lot.

New data base “patching” procedures (map feature-based) hold promise for

generating the updates for just the areas affected, rather than overlaying the

entire set of layers.

Even if the “mechanics” of applying OODBM to

Most often, these applications involve interactive processing as users

run several “what if…” scenarios. From

this perspective, habitat and sales maps aren’t composed of spatial objects as

much they are iterative expressions of differing opinions and experience (spatial

spreadsheet). For OODBM to work and

garnish data accessing efficiencies there must be universal agreement on the

elements and paradigms used in establishing fixed data objects. In one sense, the logic of a

In fact,

But another less obvious impediment hindered progress. As the comic strip character Pogo might say,

“we have found the enemy and it’s us.” By their very nature, the large

The 90’s saw both the data logjam and

So where are we now? Has the role of

MapInfo’s MapX and ESRI’s MapObjects

are tangible

Like using a Lego set, application developers can apply the “building

blocks” to construct specific solutions, such as a real estate application that

integrates a multiple listing geo-query with a pinch of spatial analysis, a dab

of spreadsheet simulation, a splash of chart plotting and a sprinkle of report

generation. In this instance,

In its early stages,

The distinction between computer and application specialist isn’t so much their

roles, as it is characteristics of the combined product. From a user’s perspective the entire

character of a

As the future of

Observe

the Evolving

(GeoWorld, March 1999, pg. 24-25)

A couple of seemingly ordinary events got me thinking about the

evolution of

I recently attended an open house for a local

The expanded community has brought a refreshing sense of practicality and

realism. The days of “

That brings up the other event that got me thinking. It was an email that posed an interesting

question…

“We

are trying to solve a problem in land use design using a raster-based

The problem involves “map-ematical reasoning” since there isn’t a button called “identify

the most suitable land use” in any of the

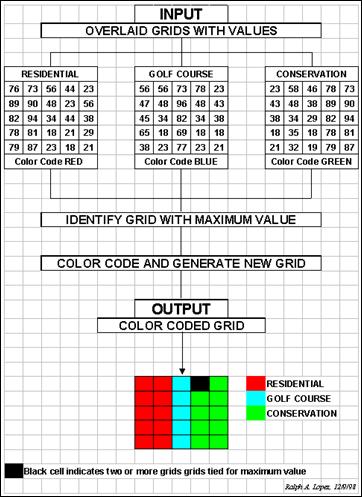

Figure 1. Schematic of the problem to identify the most suitable land use for each location from a set of grid layers.

That’s simple for you, but

computers and

Step 1. Find the maximum value at each grid

location on the set of input maps—

CMD: compute Residential_Map maximum Golf_Map

maximum Conservation_Map for Max_Value_Map

Step 2. Compute the difference between an input map and the Max_Value_Map—

CMD: Compute Residential_Map minus Max_Value_Map

for Residential_Difference_Map

Step 3. Reclassify the difference map to isolate locations

where the input map value is equal to the maximum value of the map set

(renumber maps using a binary progression; 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc.)—

CMD: Renumber Residential_Difference_Map for Residential_Max1_Map

assigning 0 to -10000 thru

-1 (any negative number; residential less than max_value)

assigning 1 to 0 (residential value equals max_value)

(Golf_Max2_Map

using 2 and Conservation_Max4_Map using 4 to identify areas of maximum

suitability for each grid layer)

Step

5. Combine individual "maximum" maps and label the “solution” map—

CMD: compute

Residential_Max1_Map plus Golf_max2_Map plus Conservation_Max4_Map

for Suitable_Landuse_Map

CMD: label Suitable_Landuse_Map

1

Residential (1

+ 0 + 0)

(Note: the sum of a binary progression of

numbers assigns a unique value to all possible combinations)

OK, how many of you map-ematically

reasoned the above solution, or something like it? Or thought of extensions, like a procedure

that would identify exactly “how suitable” the most suitable land use is (info

is locked in the Max_Value_Map; 76 for the top-left

cell and 87 for the bottom right cell).

Or generating a map that indicates how much more suitable the maximum

land use is for each cell (the info is locked in the individual Difference_Maps; 56-76= -20 for Golf as the runner up in

the top-left cell). Or thought of how

you might derive a map that indicates how variable the land use suitabilities are for each location (info is locked in the

input maps; calculate the coefficient of variation [[stdev/mean]*100]

for each grid cell).

This brings me back to the original discussion. It’s true that the rapid growth of

However, in many instances the focus has shifted from the analysis-centric

perspective of the original “insiders” to a data-centric one shared by a

diverse set of users. As a result, the

bulk of current applications involve spatially-aggregated thematic mapping and

geo-query verses the site-specific models of the previous era. This is good, as finally, the stage is set

for a quantum leap in the application of

______________________

(Back to the Table of Contents)